University of Virginia, 2023

52” x 30” x 25”

Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Red Color Concentrate

Chair No. 7, funded by the Jefferson Trust, examined the robotic 3D printing of PLA to make a 1:1 scale chair. It aimed to establish a circular plastic production of architectural furniture to reduce plastic waste. Additionally, an integrative computational tool was developed to assist with form generation.

The circular use of plastic

Plastic materials in various forms—including thermoplastics, thermosets, and elastomers—are commonly used in building construction today. They are used indirectly as construction molds or directly as building facades or interior spaces. Recent use of plastic composites such as carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP) presents the undeniable potential of their use in building structural elements (Menges and Knippers 2021). However, the long biodegradation of petroleum-based plastic necessitates changing the mindset about plastics use.

Novel approaches like Cradle-to-Cradle (McDonough and Braungart 2002) and Circular Economy (Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2013) propose the design and implementation of a sustainable approach in manufacturing. Circularity in production challenges the linear model of economy, “take-make-waste” (Leonard and Conrad 2010), by investing in the efficient use of resources through innovation in repurposing waste materials.

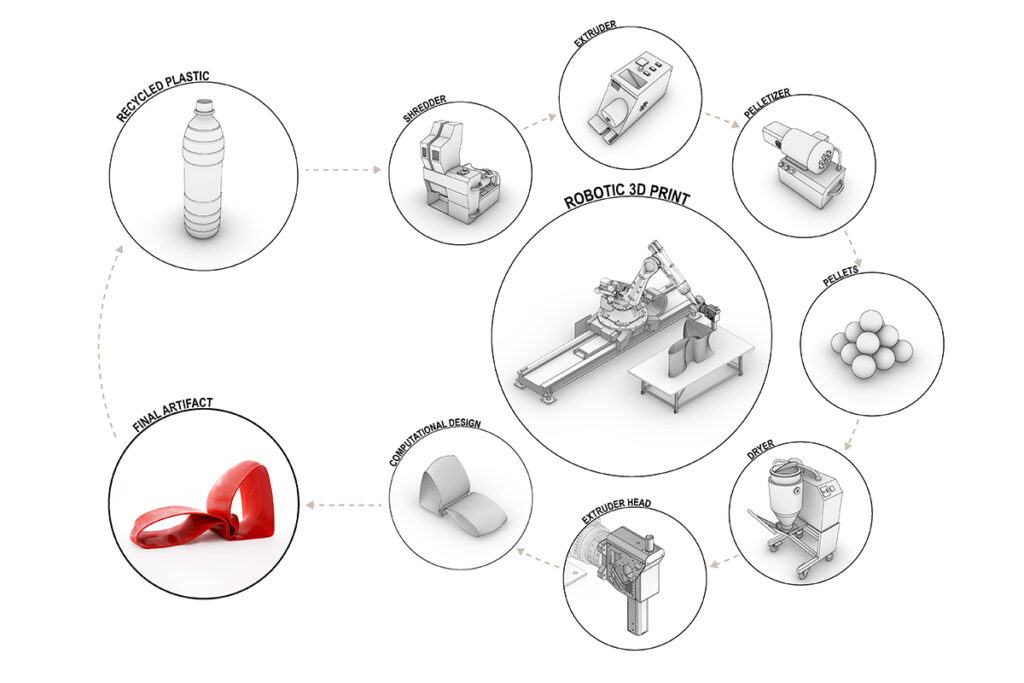

From shredding to extruding thermoplastic

The general awareness of the negative environmental impacts of plastic waste is effective in generating movement towards implementing circularity in plastic waste management. This includes adapting industrial-scale plastic recycling processes to smaller scales to fit on a desktop. Recycling plastic waste, after washing, includes shredding plastic waste into small pieces and melting them down to produce filaments. These filaments can be used directly or pelletized. This process helps close the circle of plastic waste and enables the design of a closed-loop system that includes each process from manufacturing plastic objects to reusing plastic waste.

Additionally, applying a robotic industrial arm in 3D printings allows designers to design beyond the imposed dimension of a 3D printer’s bed. This changes 3D printing from just prototyping towards printing building elements at a 1:1 scale.

Case Study: layer-by-layer robotically 3D printed chair

One of the plastic types that is widely used in 3D printers at the University of Virginia School of Architecture is Polylactic Acid (PLA). PLA is considered Number 7 in the plastic waste categorization. Its biodegradation and low level of toxicity make it popular for prototyping architectural models. However, a huge amount of failed 3D printed prototypes is considered landfill waste. A reclamation process for this type of plastic would decrease this waste and can be extended to other non-toxic plastics such as Numbers 1 and 5.

Robotic Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is a layer-by-layer process of extruding polymers such as PLA. This layer-based process might differ from 3D printing with supports in that complex geometry is rationalized to have 3D printed supports for overhanging sections. Thereby, printing layers are designed to act as structural supports for upper layers. This manufacturing process reduces 3D printing time. Rationalizing complex geometries requires the integration of materials and fabrication constraints in design processes at the earliest stage of design.

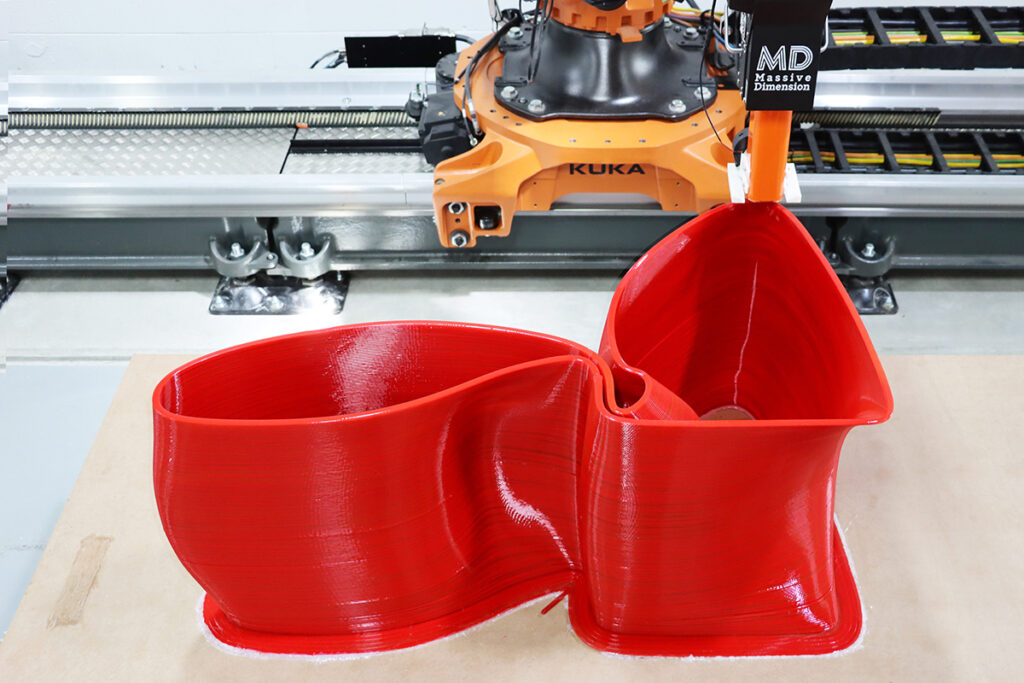

This case study, a 1:1 scale chair, tested the formation to materialization stages to establish a circular plastic production of architectural furniture by 3D printing PLA. An integrative computational tool was developed to assist with form generation. This tool integrates three main parameters involved in the production of a robotically 3D printed chair: PLA’s mechanical and structural properties, limitations of the robotic fabrication system (KUKU KR120 R2700-2) and pellet extruder head (MDPE10, Massive Dimension), and selected individual human parameters. Tilley (2002) in “The measure of man and woman” identified the human factors of designing ergonomic chairs (Tilley 2002). These design factors can be abstracted to user-based parameters to individualize each product, such as the height and width of the individual human body.

A series of experiments was conducted to identify the required parameters for 3D printing PLA palettes, such as the robot kinematic velocity, the temperature, and the revolutions per minute (RPM) of the extruder head. These experiments used a fixed 5mm nozzle to determine other parametric variables. The experiments included determining the inclination angles, width, and height of each 3D printed layer. These parameters shaped a parametric space as a design solution space for designing a chair.

The result is an ergonomic chair, robotically 3D printed with PLA. In order to change the color of the chair, red color concentrates (3DXTECH) were added. The rate of red spectrum was calculated with the amount of red concentrate by weight to the overall weight of the pure PLA. The fully automated process of 3D printing includes the automatic feeding of pellets to the robotic fabrication system. The overall process of robotically 3D printing this chair was between 14-16 hours, including everything from preparing the material to fully 3D printing the chair.

Discussion

This case study showcased the automation process of 3D printing an ergonomic chair, an everyday thing. The computational framework facilitates the integration of material properties and robotic fabrication systems, while parametrically allowing design adjustments to human parameters. The process of integrating material and fabrication parameters enables designers to exploit a design solution space curated with the specific material and fabrication system. This space, confined to the capacities and limitations of materialization processes, provides an exploratory space that monitors the constructability of the design. This encourages designers to embrace design agencies to address individuals’ needs. It provides a platform to consider human parameters as important factors of circular design. This computational interface allows designers to witness the process of formation located within their fabrication capacities.

Author and Image Credit

Ehsan Baharlou

Project student research assistants

Avery Edson, Keaton Fisher, Juliana Jackson, Eli Sobel, and Tabi Summers

Image Credit

Ehsan Baharlou, CT .lab, University of Virginia, 2023

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Melissa Goldman, UVA School of Architecture fabrication lab manager, and Dr. Trevor Kemp, UVA School of Architecture fabrication facilities assistant manager, for their profound support. The exhibitor also thanks the Jefferson Trust for funding this research project.

References

Cheshire, David. 2021. The Handbook to Building a Circular Economy. Second edition. Newcastle upon Tyne: RIBA Publishing.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2013. “Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition.”.

EPA. 2023a. “National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling.” Accessed November 22, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/national-overview-facts-and-figures-materials.

EPA. 2023b. “Plastics Product Manufacturing Waste Management Trend.” Accessed Novemebr 22, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/trinationalanalysis/plastics-product-manufacturing-waste-management-trend.

Faircloth, Billie. 2015. Plastics Now: On Architecture’s Relationship to a Continuously Emerging Material. London, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Leonard, Annie, and Ariane Conrad. 2010. The Story of Stuff: How Our Obsession with Stuff Is Trashing the Planet, Our Communities, and Our Health–and a Vision for Change. 1st Free Press hardcover ed. New York: Free Press.

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. 2002. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. 1st ed. New York: North Point Press.

Meikle, Jeffrey L. 1995. American Plastic: A Cultural History. New Brunswick N.J. Rutgers University Press.

Menges, Achim, and Jan Knippers. 2021. Architecture Research Building: ICDITKE 201020. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Tilley, Alvin R. 2002. The Measure of Man and Woman: Human Factors in Design. Rev. ed. New York: Wiley.